|

|

|

Photographs (left to right): Edelweiss, Adirondacks, New York, Jellyfish, Florida; Forget-Me-Not's, Rush, New York

The Wampum Belt Archive

Wampum Belts in Paintings and other Art Media

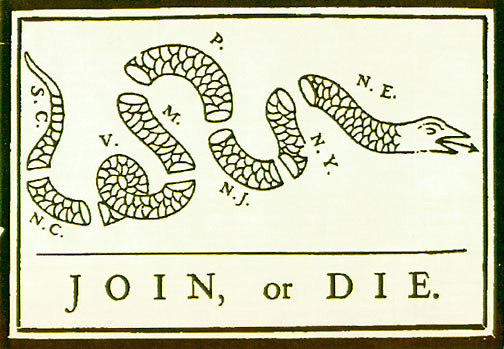

Albany Plan of Union Belt (1754)

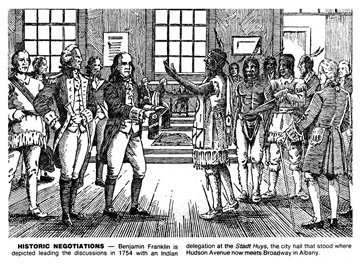

Ben Franklin with the wampum belt and the Mohawk King Hendrick at the 1754 Albany Plan of Union. This later caused Franklin to suggest the colonies to unite.

Graphic of hypothetical belt in drawing (Hamell, 2021).

Description

In the early 1750s, rivalry between England and France over who would control the North American continent led inexorably to what is known as the French and Indian Wars. This conflict lasted from 1756 to 1763, and left England the dominant power in the area that now comprises the eastern United States and Canada. Aware of the strains that war would put on the colonies, English officials suggested a "union between ye Royal, Proprietary & Charter Governments."1 At least some colonial leaders were thinking along the same lines. In June 1754 delegates from most of the northern colonies and representatives from the Six Iroquois Nations met in Albany, New York. There they adopted a "plan of union" drafted by Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. Under this plan each colonial legislature would elect delegates to an American continental assembly presided over by a royal governor.The plan is noteworthy in several respects. First of all, Franklin anticipated many of the problems that would beset the government created after independence, such as finance, dealing with the Indian tribes, control of commerce, and defense. In fact, it contains the seeds of true union, and many of these ideas would be revived and adopted in Philadelphia more than thirty years later.fter the plan was unveiled, the Crown did not push it since British officials realized that, if adopted, the plan could create a very powerful entity that His Majesty's Government might not be able to control. The royal counselors need not have worried; the colonists were not ready for union, nor were the colonial assemblies ready to give up their recent and hard-won control over local affairs to a central government. That would not happen until well after the American settlements had declared their independence.According to George Hamell (2012):

The engraving and the event purportedly depicted are purely hypothetical. It appears to be based upon an imagined meeting between Franklin and Hendrick that was painted as a mural in the old State Museum in Albany in the early 1900s. There are records of the Albany Congress which may describe wampum belts being past and by whom to whom, but the Congress was and for representatives of the colonies and not Indian nations.

Franklin's Albany Plan of Union was based upon the organization of the seven United Provinces of the Netherlands who won their independence from Spain in 1579. The confederated provinces took as their seal a rampant crowned lion holding a sword aloft in his right hand and a bundle of seven arrows in his left hand to symbolize their union and strength of union. The bundle of arrow analogy is from a story in Plutarch telling about how a Scythian king on his deathbed convinced his 80 quarreling sons to stop fighting among themselves. Representations of the seal of the United Provinces could be seen in New Netherland and in Fort Orange-Beverwijk in the 17th century, and even on Dutch coins, at least three of which were used as pendants by the Mohawks in the 1630s.

The New York Colony's Anglo-Dutch Indian commissioner reminded the Mohawk in 1690 of this analogy after the French attack on them when the Mohawk came to Schenectady for support; Sir William Johnson did so again in 1759 using the analogy of the Roman fasces; and the American Anglo-Dutch Indian commissioners also reminded the Iroquois of this analogy at the beginning of the American Revolution. Despite an assertion to the contrary, the Iroquois did not teach this analogy to the Dutch, English, and French. Besides anyone who has collected kindling for a fire knows that it is much easier to break the kindling one stick at a time.

The Dutch of Albany and New York City were well aware of the organization of the government of the confederated United Provinces, largely through a book published by Sir William Temple in the late 17th century. Temple was the British ambassador to the Hague. Franklin was familiar with this book; he cataloged the Library Company of Philadelphia's copy in the 1740s and he published extracts of it in one of his monthly magazines in the 1740s also. It was also published in Dutch for the Dutch speakers of New York City. Reading these you can see that much of Franklin's Albany Plan of Union was based upon the organization of the government of the United Provinces.

Reference:

Hamell, George. 2012. Personal Communications.

Newbold, Robert C. 1955. The Albany Congress and the Plan of Union of 1754.

http://www.constitution.org/bcp/albany.htm

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Join,_or_Die

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|